| | 3/8/16 |

The

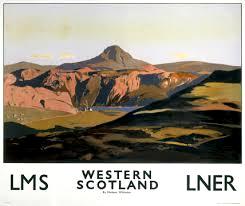

golden age of the railway posters

The

interwar period is a fascinating one, not just for its global politics (the

pinnacle of, and the beginning of the end of European global dominance) but

also art-wise. It is a period full of contradictions. For a long time the

official story as taught in art colleges was one of a relentless drive away

from representational art towards the pure abstraction of the post-war years.

It’s just that not all artists of the period fit into that picture, and recent

decades have seen a re-assessment of those that stuck to different forms of

representational art.

The story

of the inter-war (in between World War I and WWII that is) railway posters fits

in well in this debate. Publicity posters are not pure art in the sense that they

have another purpose: to sell a product, in this case seats on railway

carriages. They have a similar challenge

as do utensils and furniture: to try and be attractive as well as functional.

The

Edwardians railway companies had commissioned artists and illustrators to

produce posters to advertise their railways and their destinations, but after

the amalgamation of much of the splintered network after WWI, Royal

Academicians were commissioned by the railway companies by enlightened managers

such as Teasdale for the LNER (serving roughly the Eastern half of the

country). This led to much more

adventurous and radical designs, but there was always the knowledge that the

general public had to understand and take to the posters, otherwise there was

no point to spending money on them.

The artists

that were commissioned and produced the originals on a large format (40 x 25

inches was not abnormal), attended to the task at hand admirably. They not only created works of commercial art

that are now looked back on with nostalgic eyes, but for the times broke moulds

and saw the British Isles with new eyes, with a new palette and new

sensibilities. Beverley Cole and Richard Durack’s book on the subject (“Railway

Posters 1923 – 1947”) shows many examples from the picturesque and romantic to

the industrial and modernist.

Because of

my own preferred subject matter I am myself particularly interested in the landscape

posters by people such Frank Newbould and Paul Henry, but do look up some of

the other artists online or at the National

Railway Museum

in York (where

they keep a large collection). There are

industrial and working men’s scenes by Norman Wilkinson, Bertram MacKennal and

Stanhope Forbes, Constructivist posters by artists such as Muriel Harris and

Edmond Vaughan.

A famous

quote by Picasso I think (I’ve tried to verify it but failed) is that “painters make what they can sell, and artists sell what they make”. Whilst a nice quip, the truth has to be

somewhere in the middle surely? I do

think that the artists who designed the classic railway posters rode this

middle track, between individuality and accessibility, very successfully.

|

Be the first to post a comment.

|

1/9/15 Thoughts on visiting some

Dutch museums

On my recent visit to the

Netherlands I had the pleasure of visiting two of my home-country’s best

museums. I gave Amsterdam a wide berth this time round, but in between seeing

family and friends we managed to visit the Gemeente Museum in The Hague, and

the Kröller-Müller Museum near Arnhem. They were most enjoyable and inspiring,

both having a large collection of early 20th Century modern painting

as well as contemporary art and, in the case of the Kröller-Müller, an

excellent sculpture garden.

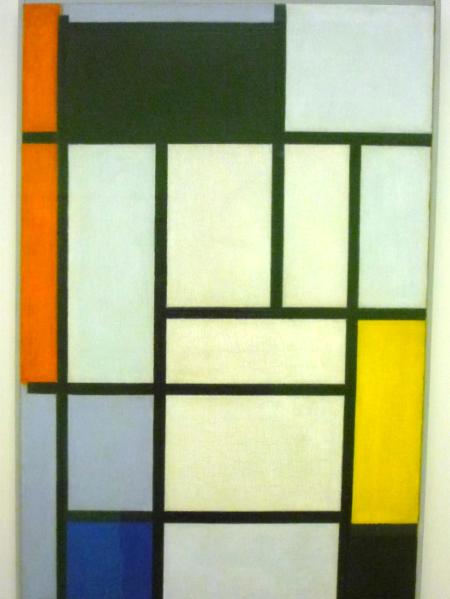

The Kröller-Müller stands out

because it holds the second largest collection of Vincent van Gogh paintings in

the world, and the Gemeente Museum of The Hague holds the largest collection of

Piet Mondriaan’s (or Mondrian) radical abstracts. But besides these gems we

were able to enjoy, as happy as pigs in ****, the works of artists as diverse

as Redon, Cezanne, Seurat, Toorop, Gris, Severini, De Chirico, Léger, Nicholson

etc.

And these were just the two museums’

own collections!

I have to admit to ignoring a

small Damian Hirst exhibit in the Gemeente Museum, but what stood out for me

was that, whilst “modern” ( as in representing Western art’s journey from

literalism, historicism and romanticism to pure abstraction) there appeared to

be a focus still on aesthetics. Aesthetics (things relating to beauty) are of

course extremely difficult to define, but I think it is fair to say that

artists up to Piet Mondriaan and Malevitch and Rothko (the travelling Rothko

exhibition was a highlight of the Gemeente Museum) were very interested in

aesthetics, even if in unconventional ways.

Artists such as Duchamps,

Schwitters, Kokoschka and many more that followed had other concerns, be they

to shock, to advocate revolution, or promote reflection, but aesthetics wasn’t

their main concern. There is nothing

wrong in that, but it does feel that to be interested in aesthetics in art has

become not just circumspect in art colleges and amongst art prize panellists

but just not done. In the process the

modern art establishment runs the risk of being just as conservative as the 19th

Century know-it-alls who condemned the first independent Impressionist

exhibition.

Anyway, we enjoyed our trip

through 20th Century European art spread over two Dutch museum

enormously, and I hope it will inspire me in my practice for a long time to

come. |

Be the first to post a comment.

|

4/23/13 |

But

is it Art?

I was talking

recently to a friend who completed a Falmouth College of Art’s degree course

and he described how much academic work was involved in completing an arts degree

these days. Lengthy essays have to be

written, and the various theories about what art is and what meaning it has

have to be studied and elaborated upon.

All very good and well, but what if you just love creating things but

are not very academic? Surely art

history is full of (mostly undiagnosed) dyslexics, academically

underperforming, emotionally damaged, stubborn or just plain rebellious individuals?

Wouldn’t most of these have been screened out and rejected by current art

degrees such as the above?

I’ve been reading

Cynthia Freeland’s excellent “But is it art?: An introduction to Art Theory”. I’m loving it, intend to finish it, and then

to read no more about art theory for some time after, because, frankly, how

much theorising about art can one really handle? And how much does it help one’s

practice?

But, the book has

triggered thinking, as a good book should, and Ms Freeland, in a post-modern

non-linear way, goes through the various ideas and definitions about what art

is or is thought to be over the centuries. Plato and Aristotle get a mention,

as do Hume and Kant, before more recent art philosophers like John Dewey and Arthur

Danto are reviewed. The older

definitions heavily depend on a notion of objective beauty, but the more modern

ones appear to get their knickers in a twist, or are extremely vague. This is not surprising considering the complexity

and diversity of modern art. For

example, Danto helpfully concludes that “a work of art is an object that

embodies a meaning” and “nothing is an artwork without an interpretation that constitutes

it as such”.

I’m always for

simplifying things wherever possible, as in my view complexity generally points

to confused understanding. Why not have

a negative definition of art, where positive definitions fail, that is to say,

define what art is not, and what is left falls in the category of art?

Firstly, art

appears to be (on this planet anyway) a human product. Animals share with us characteristics like

the urge for survival and procreation, as well as playfulness and idleness, but

I’m not aware of animals creating what we would call art. This is important, as it points to art being

a defining element of what it is to be human, as opposed to us being a mammal

alongside other mammals, just more successful at survival and procreation than

the others.

But, as Cynthia

Freeland discusses at length in her book, we tend to incorporate ornamental religious

objects from historic and non-western cultures into our cannon of what is art, even

though the original producers may not have seen them as art. And we increasingly include creative ideas

and intentionally provocative or thought provoking works into the pantheon of

what is true art, even if they have (for example) required little technical skill

to produce them.

This is why I

feel a negative definition of art is more useful than a convoluted and complicated

positive definition. What about this one: Art

is an intentionally made work not made for the purpose of survival, procreation

or play. I’ve only added play

because play is so clearly displayed by many animal species, and whilst

delightful, it does not appear to me to fall under the category of artful

expression. It does have in common with

art however that it has no direct bearing on survival (but no doubt an indirect

one).

The qualification

that is needed on the above is that many items, products, etc. are made with a

utilitarian purpose (ultimately with survival in mind) but have been made

beautiful or have been beautified. This

roughly equates to our current understanding of “crafts” and “design”, and it

is the non-utilitarian aspects of the work that make it art.

I think the

negative definition as highlighted above is pretty complete, and is a lot

clearer than existing attempts at positive definitions. It does not completely eliminate confusion. For example, a lot of expensively ornamented,

artfully made, or individually designed objects are made to bolster the

purchaser’s status and marketability in

society, bringing it into the realm of survival and procreation. And I recently learned that Rubens’ paintings

of English monarchs were part of a diplomatic charm offensive by the Catholic

powers of Europe. This goes to show that clear boundaries do not

exist. But the general thrust of my argument is clear:

From sharks in

formaldehyde (Damien Hirst) to abstract coloured squares (Piet Mondriaan) to prehistoric

Cycladic stone figurines, all these works had a cultural meaning and value (as defined

by their times) that went beyond pure survival, procreation or play. Beyond that all definitions of art become very

wordy and speculative.

|

Be the first to post a comment.

|

4/20/12In the last UK budget the chancellor of the exchequer, George Osborne, announced that he was planning to put a cap on tax deductible donations to charities. He alleged that there was evidence that some rich people with the help of their accountants were using certain charities as a tax dodge. Shortly after this news broke responsible charities were rolling over each other to warn that their income and therefore charitable activities could be seriously affected by this new blanket proposal.

I like this debate because there are so many aspects to it. Why do we pay tax? Why can't we choose what our tax is spent on? Are non-profit organisations possibly providing better value for money than the state can?

Having been brought up in the Netherlands, but having lived in the UK now for some 20 years, I am acutely aware of the difference in national attitudes towards taxation. The two nations have in common a protestant history that places a high value on contributing to society, and doing something good with one's money. But the medieval origins of taxation are quite different. In the simplest terms, the English were asked to fork out money to pay for their monarchs' foreign wars, and the Dutch were asked to pay up to build dikes against the water and to keep them in a good state of repairs. I suspect that the two nations' quite different attitudes to taxation goes back all the way to these ancient origins.

Taxation for many centuries was not seen as the panacea for all of society's ills, and only grudgingly accepted for special purposes. The contemporary welfare state with its high taxation levels is a relatively new phenomenon. I don't want to debate here the merits of high or low taxation societies, but I think it's only realistic to note that the state has an interest in promoting its own importance and so justify its size.

I think we need to see George Osborne's planned clampdown on gifts to charities in this light. This intervention would not have occurred if there hadn't been the 2008 bursting of the credit bubble, and the subsequent squeeze on government income (and increased demand on its services). The charities and the state have become competitors for the same money stream. The chancellor himself admitted that there are only a few known "dodgy charities", and those could be dealt with in a much simpler way than to overthrow the whole charitable giving framework.

But what if we assume that most charities do essential work that otherwise in a civilised society would have to be undertaken by the state, probably at higher cost and with less job satisfaction? And what if we dream a bit, and envision a society where people tax themselves voluntarily, and lots of functions of the state are taken care of in different, less top-down ways?

Before you say: that sounds like David Cameron's "Big Society" idea, do remember that people on the left also have often argued that they should be able to target their tax money, i.e pacifists and anti-militarists have long argued that their taxes should not be used for the army. So the desire to have a say and direct one's money to goals that the donor finds worthwhile has floated around on both sides of the political spectrum.

And tax experts know that to a large extent taxation is already voluntary, for better or for worse. The UK income tax rate of 83% in the 1970s was abolished not because it was ethically unsound, but because it was counter-productive and didn't work. The same doubts exist about the 50% income tax rate. Large corporations, whether one likes it or not, have a certain freedom to base their operations where they can make money and remain competitive. Because of this the Inland Revenue reasons with and sometimes cajoles large companies rather than using enforcement through tribunals and courts. Again: in practice there is an element of voluntarism already existent within the corporations tax system.

Whilst we are still some way off from a voluntary society with voluntary contributions, I do believe that the future is voluntary. For this reason alone I believe that the UK government's attempt to get their hand on more of the money given to charities is counter-productive and out of step with the times.

|

|

Be the first to post a comment.

|

2/25/12I'm reading Malcolm Gladwell's bestselling collection of essays "What the dog saw" and I am rather impressed with the man's breadth and width of knowledge. He tackles all kinds of subjects, which on the surface appear boring, yet he manages to shine a new light on them and make them fascinating. A rare talent...

In two of the chapters Malcolm delves into the ENRON scandal of 2001, when one of the most lauded American energy corporation suddenly went bankrupt. It has since paled in significance and size with the banking and credit crisis of 2008, but it was big, and, Malcolm argues, if the true lessons of the ENRON debacle had been learnt, the 2008 crisis need not have happened.

ENRON stood out, not because it stood out as sleazy, corrupt or old-fashioned, but because it was inspired by modern management theories to hire the most talented staff from the best universities, and pay them top dollar. They also gave these talented department managers much more freedom to follow their hunches, believing that this would lead to the most advanced business practices, and hence highest profitability. These practices were strongly advocated by management consultants McKinsey at the time, which is one of the reasons why ENRON had such a good name.

ENRON's exposure and sudden downfall were caused by two practices that were quite common, but poorly understood by the general public: mark-to-market accounting and Special Purpose Entities (SPEs). Mark-to-market accounting means that the profits of projects that haven't come to fruition yet (and may never happen) are shown in the company's financial statements, and are used by shareholders and others to estimate the company's value and therefore share price. SPE's are soft loans by 3rd parties to the company to enable it to expand and fund new investments, that enable the company to avoid having to go to traditional lenders, who, seeing a company that is rather exposed, would charge a higher interest. The problem is, that these 3rd parties are kept happy with a stake in the business, they become part owners of the business, just like a mortgage company owns your house.

You can see that once all these mechanisms are in place (with the documentation running into thousands of pages), it becomes extremely hard to assess in what state of financial health a company really is. This is where the similarity with the trigger for the current economic crisis comes in: The assets of lenders of sub-prime mortgages were close to worthless, the banks had next to no liquidity (cash in hand), and countries like Greece were taking financial risks on the strength of being cushioned by a strong currency kept strong by other nations. Over-exposure across the board in other words.

So how come that this could happen to a company that had hired the best talent and paid so well to keep them? Gladwell delves deeper into this question than I can do here, but he believes that a theory by psychologists Hogan, Raskin and Fazzini helps to understand what happened. They describe a type of manager that they call the Narcissist, who will take credit for things that go well, but don't take responsibility when thing don't go so well.

Gladwell also refers to research by psychologist Carol Dweck, who found that people whose self-esteem relied on their intelligence and talent, were likely to exaggerate their skill, and play down their mistakes. He then concludes that inadvertently ENRON had staffed the higher echelons of its business with these psychological types, and that his, combined with the opaque financial dealings of the company, led to its downfall.

The point I'm coming to is that there are all kinds of intelligence, and organisations ignore this at their peril. Someone who is judged to have an IQ of 60 may not be able to hurt an animal, but a "highly talented graduate" may smoothly move into research that involves vivisection. Someone with a deep appreciation of classical music can run a death camp....

Now these are deliberately extreme examples, but one can make the case for there being, for instance, emotional intelligence, musical intelligence, pragmatic intelligence, specialist intelligence, spiritual intelligence and visual intelligence. Society needs all of them.

What baffles me about the recruitment of the "highly talented" by companies such as ENRON though, is that I do not think that any child when asked "what would you like to become later?" would answer "I would like to sell oil and gas, mummy". I can just imagine a child answering "I would like to be rich", but that would be more likely when either growing up in grinding poverty, or growing up with parents who give love conditional on achievement.

It seems to me that many people who choose to work for big corporations, do so for remuneration and status, in other words for external validation, not for a particular passion for the company's services. That to me does not seem very smart. Whilst I'm not applauding the image of the struggling, eccentric artist (although there are many great specimens), I do believe that by and large artists are smart enough to do what they love and to love what they do.  |

|

Be the first to post a comment.

|

2/3/12 |

They say all publicity is good publicity. But can this truly be said of Greece recently? The country is blamed for the current crisis (a Greek word) of the Euro (named after the girl Europa who turned herself into a cow to escape the Greek god Zeus) leading potentially to a world economic catastrophe (another Greek word). The country's national office of statistics admitted to cooking the books, and the government has just made public a list of 4000 notorious tax dodgers to shame the country's wealthy to start paying their due tax. What's going on with the country that most of the rest of us know as the origin of western civilisation?

I've been reading Patrick Leigh Fermor's "Roumeli, travels in Northern Greece", and it is enlightening. Leigh Fermor is a bit of a hero of mine, and best described as a cross between Laurie Lee and Lord Byron. Having walked in the mid thirties from Hook of Holland to Constantinople he was recruited to work behind enemy lines in Greece during WWII and was influential in the abduction of the German general Kreipe with the help of the Cretan resistance. His character was subsequently played by Dirk Bogarde in the movie "Ill met by moonlight".

Leigh Fermor became a lifelong lover of Greece, and spent much of his life there. In "Roumeli" he discusses the Greek's own discomfort with their more recent history. At one point he quotes a train conductor (a refugee from formerly Greek Smyrna, now Izmir) who states he is sick of the obsession with the ancient Greek, as "it makes us feel inferior". Leigh Fermor then discusses the current fashion of the Greek to call themselves "Hellenes", when for a thousand years or so they called themselves "Romaios" or "Romios", meaning Romans of East Romans. This term however lost its lustre because it became associated with the practice of a subjected people trying to survive under Turkish rule. Hence even to the Greek the terms "Romaikes doulies" (Romaic doings, meaning Greek practices) became tainted with associations with the habits of a subject people to use clever but underhand practices to survive. Follows the post-independence bent for the word "Hellenes" harking back to classical Greece.

The recent turmoil and real suffering in Greece has everything to do with this recent history. Tax dodging and cooking books would have been a completely natural to a people who felt superior to their Turkish conquerors, and a habit hard to shake off in over a century of independence that saw ill-fated attempts to reconquer Istambul/Constantinople, civil war, conquest by the Germans, military coups and what not....

The Germans, who are presently resenting having to rescue the Euro currency, might understand the Greek predicament a bit better when they reflect on how much two generations of being under the Nazi and Communist yoke affected East Germany's citizens. I think the comparison is not idle.

In the mean time the rest of the western world could do with re-appraising the Byzantine (East Roman) world which, much more than the ancient Greek civilisation, lies at the root of modern Greece.

|

Be the first to post a comment.

|

1/27/12The Independent on 23 January featured an article on The London Art Fair's French artist/scientist Paul Tresset. His robotic arm (made at a cost of some £300) produces portraits of people by scanning them and translating them into portraits. The robot arms swivels and creates a arty looking, attractive likeness of the person it scans ("the sitter"). This re-opens a debate that has simmered ever since the invention of the camera: if a machine can reproduce a likeness why bother with art and individual artists? The difference here is that the end result of the robot Rubens' efforts has the erratic creative lines that we associate with creativity. But it is actually the result of a £300 program that with a bit of attention could create a less "artistic looking" and more "exact" result. Questions abound...

What is the difference between a machine that creates a drawing with erratic lines that look like what we've come to associate with a free-spirited artist and the real thing? But also: what is the difference between this particular robot and a photocopier with someone placing their private parts on top of it (or any other part of their anatomy)? Or a camera?

Not that much I would say to the second question. Photo-editing software can also turn any photo into something that looks like a textured painting made with palette knife. But that doesn't necessarily let artists breathe more easily in response to the first question.

What gives the current robot ("worker" in its original Slavic meaning) it's publicity value is it's erratic/creative use of lines, which ever since the invention of photography has delineated artists from "mechanical" photography.

Apart from Rembrandt's sketches and etchings in the 17th Century, we have to wait until after the invention of photography before artists started to use "inexact" lines to distinguish themselves from the new all-conquering camera. But then of course soon after photographers started to manipulate their shots to create startling results and get away from faithful renderings of reality. Photography became creative and joined the arts.... All very confusing....

Whilst my work is currently largely hand-made (and I love that) I am not dismissive of mass reproduction and technology aided creativity. I've been particularly impressed with what can be done with programs like Photoshop on screen. All of this is an interaction with and blurring of the boundary between man and machine, which is fine by me. What maybe Paul Tresset's Rubens Robot achieves is a lowering of the man-created distinction between "repetitive machine" and "artistic genius", and that may not be a bad thing.

|

Be the first to post a comment.

|

1/11/12 |

What strikes me about revisiting 19th Century art history is that there is so much more going on than the linear art history from only a few decades ago, and this re-evaluation continues into the 20th century. There are a lot of streams and tendencies going on.

But returning for now to the more familiar story, there is a lot more happening before the Impressionists came along, and they certainly had their groundwork done for them before their first show of independents. Turner, already mentioned is a true one-off and so is Friedrich, but Constable also did radical work with a free brush stroke that pre-empts what was to follow. The school of Barbizon (Th. Rousseau, Millet, Courbet) is well-known, as are Jongkind and Corot.

What was radical about the Impressionists (Pisarro, Monet, Morisot) was that they went solo, they bypassed the conventional way of being shown and recognised, and eventually pulled it off. This independence and stubbornness in its turn led to a flowering of such different styles that it actually a misnomer to talk about the Impressionists as a style. How different can it get? Monet and Pisarro, Seurat and Toulouse Lautrec, Renoir and Degas: their styles are so different, and that is where the real significance lies. As a group they were soon overtaken by new movements for who they had opened the door.

It is worthwhile noting that despite their current popularity with the Impressionists also starts the separation between a large section of the public and modern art. This was made possible by both artists' stubbornness, the will to do their own thing, and the growing diversifying urban market. That didn't stop van Gogh from hardly selling a painting during his life.

With the post-impressionists individual radicalism and experimentation reach a peak (van Gogh, Cezanne, Gauguin) and colour explodes helped by new paints created by new chemistry. But again I'm impressed by the other movements that split off at the same time: the symbolists and art nouveau artists (Redon, Klimt) and the first noted "naieves" (Rousseau).

Early 20th century we then see an explosion of styles and movements (the Fauves, the colourists, Cubists, Futurists, Expressionists, Constructivists et al). The old art history has depicted these as a movement towards ever greater abstraction, but this is now generally seen as flawed. Basically on the continent anything goes from the early 20th Cy onwards, with Britain and the US lagging some 20 years behind. There are streams and influences running right through the age and any artist can choose what they wish to do and who they feel affinity with. There are clearly families of thought, for example conceptual art is hugely indebted to Dada, and self-taught naives like Wallis have opened up opportunities for many who followed.

I'm not even going to try and name landscape artists that followed or where they fit in. Some show cubist influences, others return to a super realism or a magical realism. The field is just to wide to capture.

One last point I would like to make however is that with the advent of Modern Art (capital letters!) a second split was created other than that between the general public and the new art movements: the distinction between art and illustration, generally with an implied hierarchy of the former being of a higher order. But when we realise that the last century's linear story of art was never real in the first place, it makes it easier to see that the format of illustration is another creative outlet for outlets, and the work created, often in mass media, is as worthy of attention as individual works hanging on gallery walls or in whichever modern format. I'm often taken aback by the quality of work created just to illustrate a one-off news paper article in a weekend magazine. Artistic diversity in a diverse market is the order of the day, and that's how it should be.

|

Be the first to post a comment.

|

1/10/12 |

Landscape painting is seen by a large part of the public as the core of art practice. The cliched image of the artist, with easel and baret, painting outside in some beauty spot seems hard-wired in our collective consciousness. Amateurs aspire to it to probably to the same extent that modern art rebels against it, and it is easy to see why. But I love landscape: walking in it, cycling in it, flying over it, opening a bottle of wine in it, and painting it.

The funny thing about landscape painting, despite the cliched image, is that it is a relatively recent addition to a the art pantheon, and gained a relatively short period of dominance (romantics and impressionists) to be now consigned to a kind of sub-status in the modern art world. They certainly won't teach it at art college, although I have noticed lots of art students returning to it after graduation....

Let me indulge you in a short tour of my favourite artists in this genre: Sticking to western art (the Chinese were there earlier as in most things) it is hard to find landscape artists before the Renaissance, then landscape, clearly enjoyed by the artist, turns up as a backdrop mainly to mythological of religious subjects (Giorgione, Bosch, Altdorfer). To my mind Brueghel the Elder was the first however to make the landscape undeniably the subject rather than an ornament to a primary subject. In his "Hunters in the snow" and "Winter landscape with a birdtrap" the artist is clearly indulging his love for the landscape, and, quite unusual for his time, painting Northern European scenes rather than fanciful Holy Lands or Italianate views.

The development of the landscape than stays in Northern Europe with the genre for the first time gaining respectability in the Dutch Republic in the 17th Century, where a whole raft of artists supplied the rich burghers with scenery: Rembrandt did wonderful sketches and etchings; van Ruysdael, Koninck, Seghers, Cuyp and van Goyen are just a few of the artists worth mentioning. They all paint in the Northern baroque claire-obscur style of the day.

Where landscape surfaces in Southern Europe it remains mainly a backdrop to religious or mythological themes, with France offering a kind of halfway house. Noteworthy are Poussin and Lorrain (not so keen) and Watteau (I'm a fan).

It is in England though that landscape develops further, first with wholesale importation of Dutch works, then growing into an English style of its own. It's worthwhile noticing the impact of religion and class on the art of nations: to my eye the English landscape of the 18th century and early 19th Cy (Gainsborough, Constable) has a distinct Anglican feel about it compared with the more prosaic, even dour Dutch art.

Like in the Netherlands the growth of an affluent middle class allowed a growing number of artists to carve out a living outside of court and noble patronage, and this had an impact on the choice of subjects. Landscape fits in the increasingly utilitarian and rationalist outlook of the period. There is Wilson doing romantic mountain scenery in Wales (a possible source for thousands of poor imitations), and Sell Cotman and Towne being important in the development of watercolour. Other names worth mentioning are De Wint, Cox (we're well into the 19th C by now), Glover, Barker and Chrome. Some of it is a backward looking (with hindsight) but all of these artists have in common that in this Romantic era they choose landscape as a subject in itself. One of the advantages of post-modernism in the arts is that we can now look at the 19th century as a creative and diverse period in its own right, rather than in a teleological way seeing it only as leading up to the Impressionists. As a result we can look at and admire artists like Friedrich, Turner, Daumier and so many others with fresh eyes. There is so much diversity out there, and that in many ways can be seen as a precursor to the current situation, where in my eyes, anything goes.

Illustration takes off in a big way (Dore' springs to mind), orientalism (Roberts, Johnson) and what we now think of as high Victoriana (Becker in Britain, Cole and Bierstadt in the US), but also the Prerafaelites emerge (although less relevant to this subject) and many other individual artists. The message to take from this is that lots of movements and trends were happening, a lot of them survived the onslaught of Impressionism and Postimpressionism to live another day. (to be continued) |

Be the first to post a comment.

|

12/20/11I have been buying some equipment to help me frame my own work. I learnt years ago that framing is actually one of the hardest things to do well, and have experienced carpenters have told me they've struggled with it. That means that one is well justified to treat these tools with respect, because bodged frames look bad and can easily scupper a sale of a good painting.

I have to admit that I have been quite ambivalent about tools in the past. On the one hand I have oggled at and admired beautifully made implements such as wood carving sets, billhooks, mattocks and the like. On the other I have been less than respectful about modern technology, the equipment that builds our cities, bridges and even spacecraft. I can now see that they are all related and extensions of the first primitive poking stick or flint axe our ancestors used.

As I type this on a keyboard, watching a screen and soon sending this off into the ether thousands of small inventions and innovations contribute to this effort that you are now reading. Isn't that staggering? A keyboard, a PC, an orbiting satellite, these are of course as much tools as are an inkpen, a palette or a lino-cutter.

The amazing thing is, and that is what I love about tools, that in tools function informs form, but doesn't dictate it completely. A vase needs to be able to hold water, a pan needs to be able to cook food, but within those perimeters there is the scope to create a beautiful object, and so design is born, and therefore art.

The prehistoric beaker people in NW Europe created beautifully shaped and ornamented pots thousands of years ago, but the ornamentation was surplus to requirement. No doubt the potters got joy out of it, and the consumers of the day enjoyed bringing beauty into their lives in the same way we do today. Steve Jobs enjoyed adding beautiful fonts to his Apple Macs and we now enjoy the flexibility of a choice of typesets. The continuity in humanity baffles me and is encouraging.

Ornamentation aside another wonderful thing about tools is that in many cases (but not all) functionality creates a beautiful object quite by chance. An aeroplane looks a bit like a bird. An arrow needs to be balanced and stable to do its job. A flint hand axe needs to be tear shaped. And have you ever driven past an oil refinery in the dark? Ignoring pollution issues here for a moment, they are staggering pieces of modern art, but completely unintentional. The wonders and paradoxes of civilisation.... |

Be the first to post a comment.

|

Previously published: |

|

|